Invasive alien species are one of the major drivers of biodiversity loss, and cause dramatic, and in some cases irreversible changes to ecosystems. They can produce substantial environmental and economic damage, and their negative effects are exacerbated by other factors of biodiversity loss such as climate change, pollution, habitat loss and human-induced disturbance.

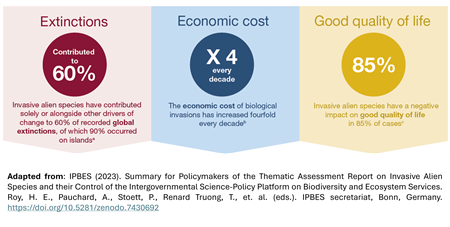

Invasive alien species have contributed solely or alongside other drivers to 60 per cent of recorded global extinctions and are the only driver in 16 per cent of documented global extinctions. Their impacts occur through different interactions, such as out-competing or predating upon native species, hybridization, transmission of diseases, or biofouling. They can change the community structure and species composition of native ecosystems directly by out-competing indigenous species for resources. They may also have important indirect effects through changes in nutrient cycling, ecosystem function and ecological relationships between native species. IAS can also cause cascading effects with other organisms when one species affects another via intermediate species, a shared natural enemy or a shared resource. These chain reactions can be difficult to identify and predict. Furthermore, aggregate effects of multiple invasive species can have large and complex impacts in an ecosystem.

Invasive species may also alter the evolutionary pathway of native species by competitive exclusion, niche displacement, hybridization predation, and ultimately extinction. Invasive alien species themselves may also evolve due to interactions with native species and with their new environment.

Besides affecting biodiversity invasive alien species can directly affect human health, causing allergies or physical injuries. They can also be vectors of infectious diseases imported by travelers or by the movement of exotic species such as birds, rodents and insects among others. Invasive alien speciesmay promote the movement of pathogen to new geographic locations leading to the emergence of diseases. Invasive alien species can also have indirect health effects on humans, such as for instance those resulting of the use of pesticides and herbicides, which infiltrate water and soil.

Invasive alien species can also negatively affect economies and infrastructure across different sectors, food and water security, and human health and wellbeing. The impacts are often felt the most by communities with the greatest direct dependence upon nature, including indigenous peoples and local communities. The global economic costs of invasive alien species have quadrupled every decade since 1970, and in 2019 the annual costs of biological invasions were estimated to exceed US$423 billion (IPBES, 2023).

The number of invasive alien species and their impacts are increasing across all regions of the Earth. Demographic, economic, and land-use and sea-use changes and their interlinkages with climate change and other drivers of biodiversity loss will continue to increase the frequency and extent of biological invasions, and the magnitude of impacts from invasive alien species (IPBES, 2023).